In 2020, Derrick Henry did what only seven other players in NFL history have ever done. He ran for more than 2,000 yards. In 2021, with a 17th game on the schedule, he’ll have a shot to break Eric Dickerson’s 37-year single season rushing record of 2,105.

But a major question looms. In a league where running backs who burn bright rarely burn for long, will Tennessee’s unstoppable force finally meet an immovable object?

Henry is only 27 years old and coming off the best year of his career, but his workload raises concerns. He’s led the league in rushes each of the past two regular seasons; his 681 carries are 119 more than the second most-used back in that span, Dalvin Cook. This is typically where NFL running backs hit a wall, at least temporarily.

“Typical” is not a word we would use to describe a tailback whose listed 240lb playing weight seems like a typo. Henry is an anomaly, a beefy runner who gets stronger as games wear on as though the rules of cardio don’t apply. In his career he’s averaged 36 more rushing yards per game in the playoffs -- after 16-ish games of wear and tear and now facing some of the league’s best teams -- than he has in the regular season.

What can the Titans (and legions of invested fantasy owners) expect from the player who established himself as the league’s preeminent runner last fall? There are reasons to believe he can keep this up … and reasons to expect he won’t.

The argument against: Henry is already beyond the threshold where running backs break usually down

There’s no shortage of examples where overworked backs fell off after a high-usage record-breaking campaign.

Larry Johnson had an absurd 416 carries for the Chiefs in his age 27/28 season in 2006, then missed half of the 2007 season to injury while his yards per carry dropped by nearly a full yard. He was never the same runner afterward. Demarco Murray handled the ball a league-high 449 times in 2014 at 26 years old. Up to that point he’d averaged 4.8 yards per carry; in the three years that followed that number dropped to 4.0. Adrian Peterson ran for 2,097 yards at age 27 in 2012, then saw his yards per carry fall from 6.0 to 4.5 the following season.

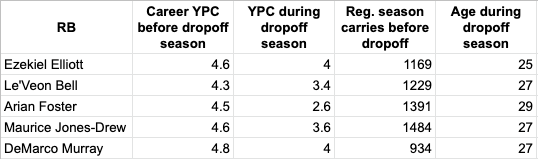

Henry’s now at 1,318 total NFL carries, more than guys like Tyrone Wheatley, Latavius Murray, and Dorsey Levens had in their entire careers. We’ve seen similarly lauded players recently fall off a cliff after hitting the four-figure club:

That’s not a hard-and-fast rule, however. LaDainian Tomlinson had more than 2,300 regular season carries before he declined at age 29. Even if Henry falls off this fall, there are examples of players bouncing back from this limit. Peterson was, of course, Adrian Peterson for roughly the decade that followed. Murray had a near-1,300 yard campaign for the Titans in 2016. LeSean McCoy had more than 600 carries in 2013-14 and proceeded to make the Pro Bowl the following three seasons from ages 27 to 29. Marshawn Lynch had 301 carries at age 27 and then got even better at age 28!

There are plenty of reasons to believe Henry isn’t cooked just because he’s by far the league’s most worked tailback from 2019-on. Most notably …

The argument for: Henry thrives when everyone else gets tired

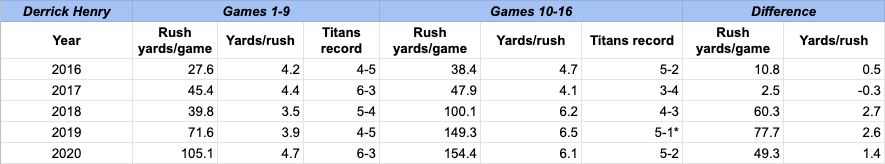

Henry’s been a postseason mainstay -- in both the real NFL and fantasy leagues -- because he’s an absolute beast late in the year. The Titans have risen and fallen with his November/December runs. With the exception of 2017, he’s delivered in spades.

*Henry was inactive for one game down the stretch in 2019. The Titans lost that game, albeit to a pretty good Saints team.

A 240-pound man should not be thriving late in the year, but it’s not unheard of on a yearly basis; Johnson did it in 2006 when his YPC jumped from 4.1 to 4.5 for the Chiefs. Elliott pulled it off in both his 300+ carry campaigns. Bell did it in 2017.

But their improvements pale in comparison to Henry boosting his rush average over six yards per carry and total output by at least 49 yards per game in THREE STRAIGHT YEARS. That’s insane, especially when you consider Murray’s YPC dropped from 5.1 to 4.2 in his All-Pro 2014. Lynch’s average fell from 4.5 to 3.9 late in his high usage 2013. Plenty of heavy-running bruisers in the Henry mold fell off, but not the gold standard.

This suggests he could still have an epic 2021 even if he starts off with some underwhelming numbers. But even if he does struggle, Tennessee is built to prop him up and give him opportunities to thrive.

For the sake of argument, let’s say Henry’s yards-after-contact number drops from a top five rate to a top 15 one in his sixth season as a pro. With 2020’s stellar line mostly intact and Taylor Lewan returning from a knee injury, let’s assume last year’s 2.5 yards-before-contact number stays intact. If he can be as good as Mike Davis (2.4 YAC last year) after encountering his first tackler he’d still wind up with a healthy 4.9 yards per carry. Prorate that over last year’s 23.6 carries per game and you’ve got 115.8 rushing yards each Sunday.

In a 17-game season, that leaves Henry at 1,968 yards, assuming he doesn’t miss any time. That’s not quite epic, but it’d still be one of the top 10 single-season performances in NFL history.

The argument against: Henry was baaaaaad in last year’s playoff defeat

This could suggest he’s getting tired. Or that teams have a blueprint to slow him down.

Henry’s postseason success came to a crashing halt last January when the Ravens effectively eliminated him from Mike Vrabel’s gameplan. He ran for just 40 yards on 18 carries. His longest gain of the day was eight yards.

Baltimore dented his impact by crowding the line of scrimmage and daring Ryan Tannehill to beat their secondary through the air (he demurred). His yards before contact dropped from 2.5 to 1.3. More concerningly, his yards after contact number plummeted from 2.8 to 0.9. He had eight carries and 21 yards in the second half, which was a slight improvement over his first two quarters but a far cry from the “I thrive when you’re tired” runner who’d dominated the regular season.

This was a wild departure from the 2019 postseason upset in which Henry led the Titans to victory with 195 rushing yards on 30 carries. Henry had also run for 135 yards against a Covid-depleted Ravens team earlier that season.

The Ravens had the secondary chops to limit the Titans’ passing attack in single coverage, leaving to a litany of seven- and eight-man boxes. As a result, 17 of Baltimore’s 18 tackles vs. Henry that game came from linemen or linebackers. Nine came from the defensive linemen in their 3-4 setup. The Ravens didn’t just win at the point of contact, but they also had plenty of gap-filling backup to slow Henry for the first time in three tries. Other opponents with similar confidence in their defensive backfields could do the same.

Fortunately for the Titans, opponents will be less likely to crowd the line of scrimmage and trust their defensive backs in man-to-man or Cover 1 situations because ...

The argument for: Julio Jones’ arrival means fewer stacked boxes and more room to run

Corey Davis had a very good year in 2020. He was not, however, Julio Jones.

Jones’ arrival from Atlanta -- at the bargain price of a second-round pick! -- not only stems the bleeding of an offseason that saw Davis and tight end Jonnu Smith depart as free agents, but likely upgrades Ryan Tannehill’s target list. As previously noted, Jones is coming off a down year thanks to injury but remains a second-level threat who creates separation downfield in a way few wideouts can match.

While it may take a while for Tannehill to build the kind of rapport Matt Ryan had with the future Hall of Famer, a healthy Jones -- even at 2020 levels -- is a boon for any NFL offense. Leaving Jones and A.J. Brown in single coverage is a recipe for disaster, even if Tannehill’s passing game is more efficient than explosive. That’s exactly what opponents would have to do in order to throw eight men in the box on plays where Anthony Firkser or Josh Reynolds enters the lineup as a third target.

With Brown and Davis on the field, Tennessee faced the fifth-lowest amount of two-deep coverages in the league last season as defenses converged on Henry. 163 of his carries -- most in the NFL -- came against eight-man boxes since opponents could take their chances downfield with Tennessee’s wideouts and, to a lesser extent, Smith.

Baltimore wasn’t worried about Davis in last year’s Wild Card game, for good reason. He had zero catches in that playoff game against the Ravens. His average depth of target was just six yards. He did nothing to stretch the field.

Jones, on the other hand, has 61 catches, 834 yards, and six touchdowns in eight career playoff games. His average target depth in 2020 was more than 11 yards downfield. Just as importantly, he pushed young teammate Calvin Ridley to new heights when both were in the lineup last fall.

Jones will still be good. Brown will be better. Combined, they’ll form one of the best 1-2 punches in the league. That’s great news for Henry -- and for every aspect of the Tennessee offense.

There are reasonable concerns about Henry’s 2021 form. Despite his heavy workload, there are several reasons to believe he’ll still be an upper crust running back this fall. While there’s been some drop off from players in similar situations, it’s not uncommon for workhorses to remain workhorses into their late 20s. Additionally, he’s Derrick Henry. His numbers paint a picture of an absolute outlier who thrives in the face of fatigue unlike anyone else in the NFL.

So yeah, Henry can absolutely keep this up. And with Julio Jones giving him a little extra breathing room, he might be even better in 2021. -- CD